Reflections on the Life of Omar ibn Said – Dr Hadia Mubarak

Dr Hadia Mubrak shares her reflections and thoughts on the life and legacy of Omar ibn Said.

In our public discourse, the term “Muslim” tends to be synonymous with words like “foreigner,” “immigrant” and “refugee.” Yet the historical reality of Muslims in America depicts a completely different portrait. The first Muslims to come to America were Africans, chained, forced into bondage and stripped of their heritage, religions, and families.

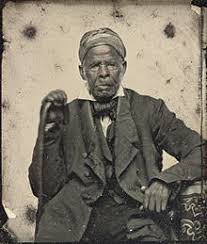

The history of Muslims in America begins with people like Omar ibn Said, a Muslim scholar who was brought to Charleston, SC in 1807 and was later imprisoned in Fayetteville, NC for running away from his slave master. A few months ago, the Library of Congress made virtually accessible his autobiography, the only one of its kind, to the world, noted in the PBS video below.As a Muslim American, I feel personally indebted to the legacy of Omar ibn Said. I cannot fathom what it must have been like for this 37-year-old Gambian scholar of Islam to arrive to a new land, forced to contend with a new culture, religion and language and be stripped of one’s freedom and identity. The autobiography of Ibn Said speaks to his faith, wisdom and perseverance.

His decision to write his autobiography in Arabic – the only extant autobiography in Arabic by an African slave – is not incidental. By writing his autobiography in Arabic, a language that neither the slave masters nor the dominant society could understand, Omar ibn Said was asserting an autonomy of identity. He, and not his slave masters, would have the final word on his own narrative. Further, Ibn Said’s reference to the 67th chapter of the Quran, the Chapter of Dominion (Surat al-Mulk), in his autobiography is revealing. It reflects the faith of a man who internalized the ultimate reality of God’s dominion over all things; it reflects the knowledge of man who recognized that the only Master in this world is the Creator of the heavens and earth and everything in between.

It is worth considering how Omar ibn Said’s mastery of the Quran paved his way to living the rest of his life honorably, removed from a life of arduous labor under ruthless conditions, to which most slaves were subject. By writing passages of the Quran in Arabic on the walls of his Fayetteville prison cell, Ibn Said was recognized by those in power to be an educated man. As a result, Ibn Said was not subject to the laws applied to runaway slaves. Saved from punishment, he was instead transferred to the home of General James Owen, the brother of North Carolina’s governor, and treated very well, according to Ibn Said himself. It was not Omar’s decision to run away from slavery nor to seek shelter in a church that turned his fate around. Rather, it was his decision to write passages of the Quran on his prison cell walls that turned his fate around, attracting the attention of state authorities.

As the Library of Congress makes virtually accessible Ibn Said’s autobiography to the world, I cannot help but wonder whether he had ever considered the possibility that millions of people would one day read his biography. As an educated, literate and well-read scholar, his decision to select high quality paper for his manuscript indicates that he was writing for posterity. Could he have imagined, however, that millions, maybe billions, would read his words nearly 200 years later? We can never really know.

The public release of his autobiography reflects the redemptive nature of history, a history in which the marginalized, the oppressed and the voiceless are given the final word. As a Muslim, I interpret this as God’s acceptance of Ibn Said in His divine favor, and God knows best.

The stories of Muslim African slaves like Ibn Said’s offer just a glimpse into a part of American history that we’ve neglected to tell. And by the way, Ibn Said’s story represents not African American history nor Muslim American history, but American history. The personal accounts of enslaved Muslims like Ibn Said, who felt compelled to publicly convert to Christianity – the official religion of their slave masters – shifts the overall story we have told ourselves about religious freedom in U.S. history. Without question, America offered refuge from religious persecution for scores of immigrants who came to U.S. shores of their own volition. Yet this was not the case for over 300,000 enslaved African men and women. The personal accounts of folks like Omar ibn Said should occupy the center, not the margins, of American history.

Dr. Hadia Mubarak is an assistant professor of religious studies at Guilford College. Previously, Mubarak taught at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte and Davidson College. Mubarak completed her Ph.D. in Islamic studies from Georgetown University, where she specialized in modern and classical Qurʾanic exegesis, Islamic feminism, and gender reform in the modern Muslim world.